Why you can trust Creative Bloq

Our expert reviewers spend hours testing and comparing products and services so you can choose the best for you. Find out more about how we test.

Content warning: this review discusses graphic violence, disturbing imagery, and mature themes in an 18+ game.

Say what you like about Romeo Is A Dead Man developer Suda51 – and his gritty, hard-boiled games have provoked Marmite-like responses in the past – but his oeuvre is the antidote to all things bland and generic. That is especially true of Romeo Is A Dead Man, which gripped me from its opening scenes by employing a welter of visual styles, then kept me enthralled thereafter with an unhinged plot and thoroughly satisfying hack-n’-shoot gameplay.

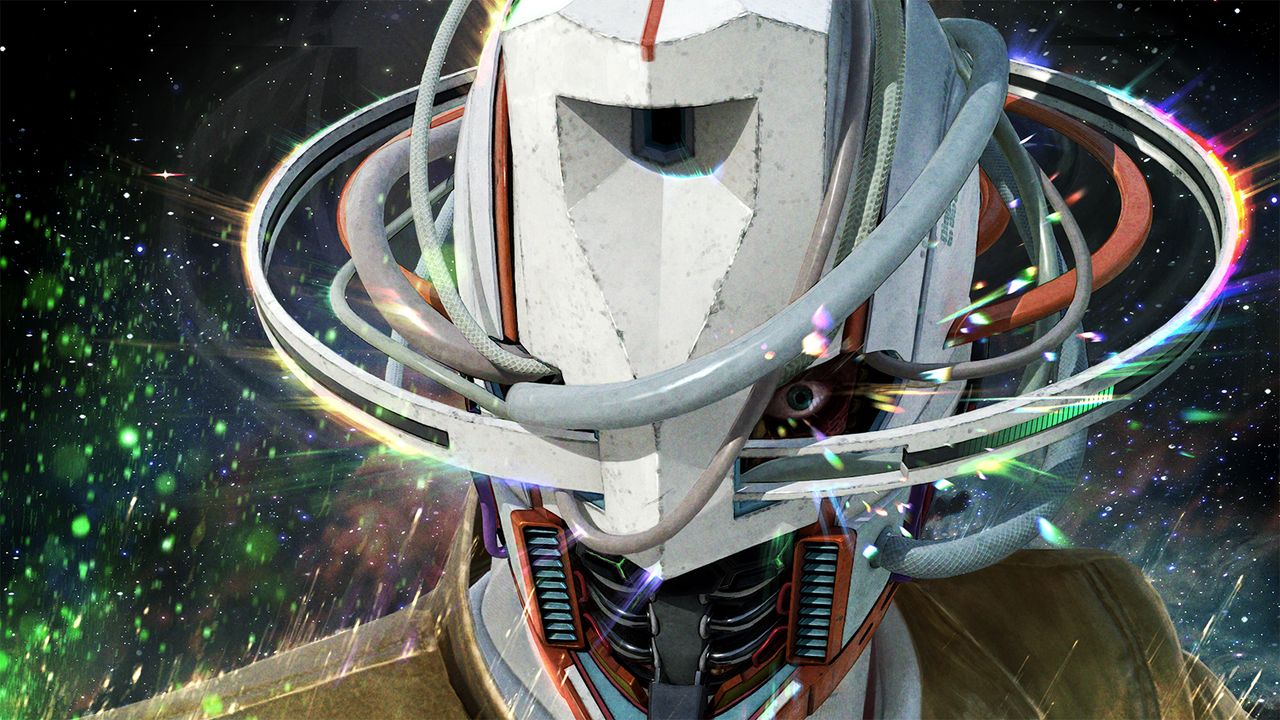

The end result is an unforgettably distinctive gaming experience, which feels particularly valuable in this age of AI slop. But the most impressive aspect of Romeo Is A Dead Man is that it somehow coalesces into a coherent whole with a (very weird indeed) form of interior logic. That’s despite the way in which it threw a smorgasbord of visual styles at me, including conventional third-person 3D, a spaceship hub rendered in classic top-down 16-bit style, other transitions and sequences offering homage to 8-bit classics, several different styles of framed comic-book art, and a whole layer of subspace apparently inspired by Tron.

For anyone fascinated by the possibilities that video games throw up in terms of supporting diverse art styles, Romeo Is A Dead Man demands to be checked out, as surely no previous game has showcased such a wildly differing set of art styles. Which is all very well, but the game’s triumph – and a testament to the improvisational genius and overall game-direction skills of Suda51 – lies in how well it hangs together as a game, when in anyone else’s hands it would have been an unholy mess.

Suspend disbelief

Curiously, one of the key aspects that melds Romeo Is A Dead Man’s clashing visuals into a coherent whole is its storyline, which sits somewhere on the spectrum between absolutely barking and totally unhinged. Its sheer ridiculousness somehow paves the way for a similar approach on the visual side.

It begins in a tiny US backwater, where Romeo Stargazer, working as a deputy sheriff, stops to investigate a body lying in the road and is ripped to shreds by a shadowy white phantom. Luckily, Benjamin, his grandad, a time-travelling boffin (possibly inspired by Rick and Morty’s Rick Sanchez), arrives to inject him in the eye with a life-support system, consisting of a helmet, a bionic arm, and a selection of light-sabres and guns. Benjamin dies in the process, but lives on as a patch on the back of Romeo’s jacket.

Soon, Romeo is recruited by the FBI’s Space-Time Department to zoom across the universe in a spaceship sniffing out the most-wanted space-time criminals responsible for causing anomalies that lead to the destruction of entire worlds. Chief among whom, it turns out, is Juliet, a mysterious brunette who, at the time of Romeo’s accident and reconstruction, was his girlfriend.

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

(Image credit: Capcom)

Romeo himself is endearingly naïve and puppyish – despite becoming aware of Juliet’s status as a literal destroyer of worlds, he remains hopelessly in love with her, which gives his quest to eliminate her peers and, eventually, her an added edge.

On the spaceship to which he is whisked when recruited by the FBI – depicted like a 16-bit game – he finds his sister and mother. The latter helps him make stat-buffing meals, while the former is in charge of growing so-called “bastards” from seeds – zombie-style assistants who help Romeo in combat, by operating as turrets, or means of weakening enemies or buffing Romeo.

A surprising amount of fun can be found on the FBI spaceship, which acts as a calm oasis between frenetic missions, and showcases a vast store of Suda51’s trademark quirky humour. Its anomaly-scanner is operated by playing a twin-axis version of Pong, while Romeo himself levels up by playing a version of Pac-Man. The FBI’s notorious addiction to bureaucracy is parodied, and campfire-style chats in the spaceship’s garden prove bizarrely compelling. Throughout the game, and especially on the FBI spaceship, an unexpectedly literary undercurrent pervades – another of Suda51’s trademarks.

Frenetic third-person action

But when reports come in regarding anomalies caused by the FBI’s Most Wanted list of space-time criminals, it’s time to descend to different places on Earth, in different time frames, so that Romeo can hunt down the baddies and defeat them in boss battles. That’s where the real meat of Romeo Is A Dead Man lies.

Its core gameplay isn’t as wildly unconventional as the rest of the game: Romeo must take down a suitably weird set of enemies using his lightsaber-like sword, his gun (there are various types, all with unlimited ammo but a slow reload), a special Blood-attack which is recharged by taking out swathes of enemies, and the aforementioned “bastards”. At times, respawn points appear, which Romeo must shoot out while under attack, and there are set-pieces in which Romeo must take out all enemies before being able to progress. Each chapter culminates in a boss-battle against the space-time baddie, who morphs into the gruesomely mutated form typical of a horror-game.

But each chapter also includes an element of puzzlement, as Romeo encounters TVs displaying a shadowy figure who engages in often hilarious cod-philosophical conversations that let him descend into subspace. Subspace corresponds physically to the surface world (although it’s rendered in shiny 1980s-neon style) and involves no fighting (until the game’s latter stages) but plenty of navigational puzzling in order to reach impassable areas of the surface world map, along with collecting parts of the Klista keys, which will open the gate behind which the boss hides. Recurring, rather Zen-like, twin stick-alignment puzzles open up new staircases and areas in subspace.

Plenty of nuance and variation

Each chapter, while following the same overall format of clearing hordes of enemies in surface space while puzzling in subspace to reach new surface areas, offers differences and nuance in its gameplay, often via additional puzzles in the surface world (some of which are pretty decent). In one chapter, stealth comes to the fore as Romeo is caught in a time loop in a creepy, abandoned hospital and must avoid a giant, galumphing enemy. In another, Romeo must collect coloured stones to open up new areas of a remote island. In that chapter, set in the 1970s, he is accompanied by Jenny, a rather endearing AK-47-toting journalist with the face of a zombie and the attire of a hippy.

While I soon learned how to deal with the different types of enemies (some must be taken out by shooting weak points from afar, while it pays to save up Blood attacks for others who have a large amount of health, for example), and combinations thereof, I never felt that Romeo Is A Dead Man’s gameplay descended into predictability. But it constantly remained satisfying – not to mention thoroughly gory (in common with pretty much all of Suda51’s games), fast-paced, and quite thrilling.

I’m pretty sure Romeo Is A Dead Man will be by some distance the weirdest game that anyone will release this year (and probably in the years to come until Suda51’s next game arrives). If you like your games to be logical and predictable, you will hate it. But if you like games that show a sort of individualist punk energy, look like nothing on Earth, make you laugh out loud, and provide some great action and decent puzzling, you’ll find that Romeo Is A Dead Man more than ticks those boxes. Even after more than 30 years of making games, Romeo Is A Dead Man might be Suda51’s best effort yet.

Romeo is a Dead Man: Price Comparison